Some content warnings before you watch: there is a sexual assault scene, some gore, but mostly just psychological distress. R rating.

Perfect Blue began as a light novel (a light novel in Japan is considered a shorter novel, generally geared towards young adult readers) by Yoshikazu Takeuchi in 1991. The english title is Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis.

The light novel is about Kirigoe Mima, an idol switching from a pure, innocent image to a more mature, risqué one. Her assistant Rumi is fiercely loyal, and determined to help Mima find success in the ways she failed as a former idol herself. Eri is Mima’s rival, looking for ways to sabotage Mima’s sweet reputation, but the antagonist is the stalker. He is an obsessive fan who sends letters concerned about Mima’s changing image.

If you have seen the film, you will notice a few differences in this description. This light novel was used simply as a guideline for the plot of the film, and I’m very thankful they chose this route. The book itself is very bland, except for some gory sequences of the antagonist skinning himself and others. There are no unexpected twists, and the characters are all very straightforward.

But this was not the only writing from Takeuchi’s Perfect Blue universe, we also have Perfect Blue: Awaken From a Dream and anthology book published in 2002, but written before the light novel. The three stories feel like fragments that would lead to Metamorphosis, rehashing the same themes in each plot. The first story Wake Me From This Dream is about Toshihiko, an incel-like, lazy idol fan, who wakes up in his favorite idol, Asaka Ai’s body one day. I find this addition of magical realism a strange addition to the universe, and kept hoping this would be some type of psychosis instead. Secondly, is Cry Your Tears, about idol Kawasaki Yuma receiving scary letters threatening her changing image… Do you see why I almost skipped this story? I found nothing new or interesting in it. Finally, we have Even When I Embrace You, about Yukiko Tsukioka, a traditional idol singer who is being stalked by a man in a creepy bunny suit. The bunny suit element was a tiny bit refreshing, even though the plot otherwise remained the same. Basically, I will never read any more of Takeuchi’s books and do not recommend them. But I am so glad they exist, because Satoshi Kon was able to get his hands on them.

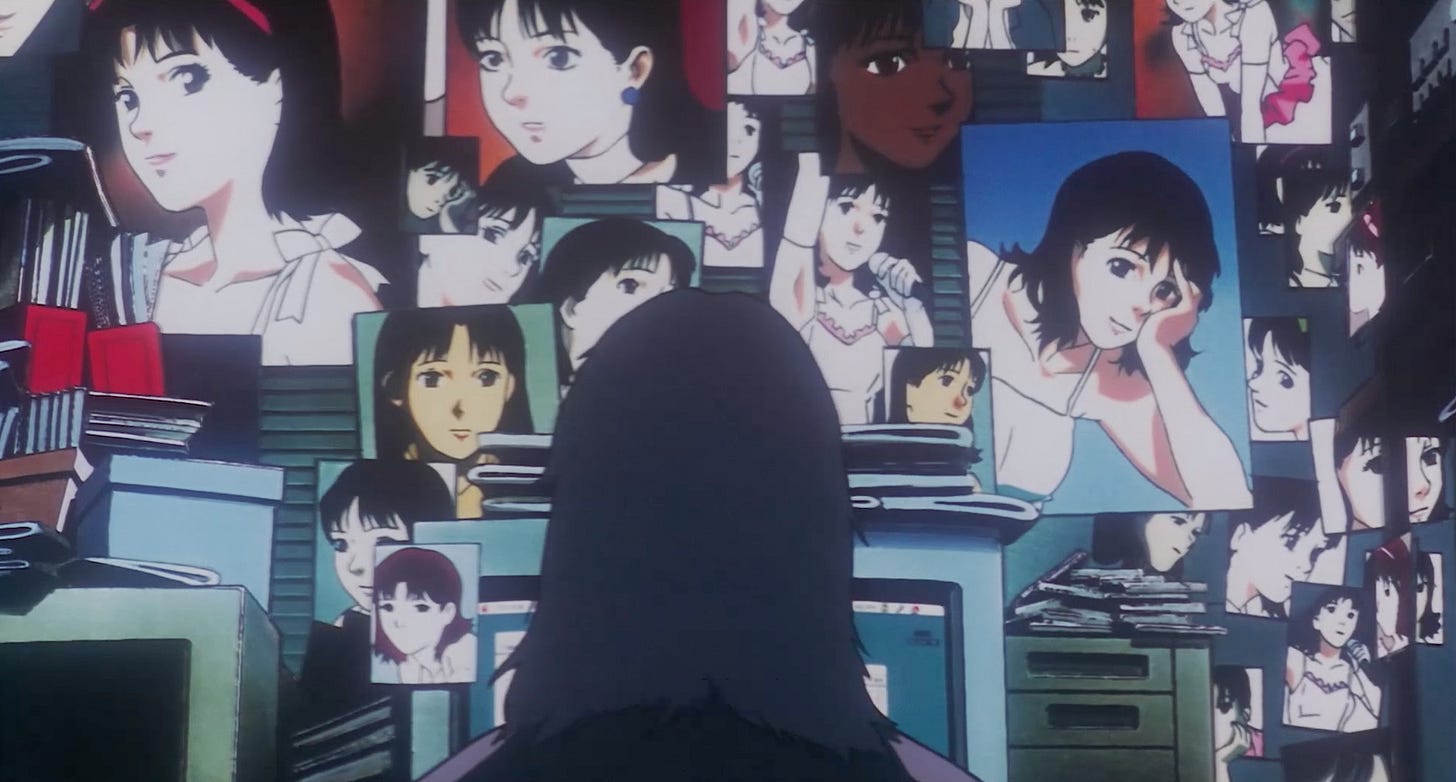

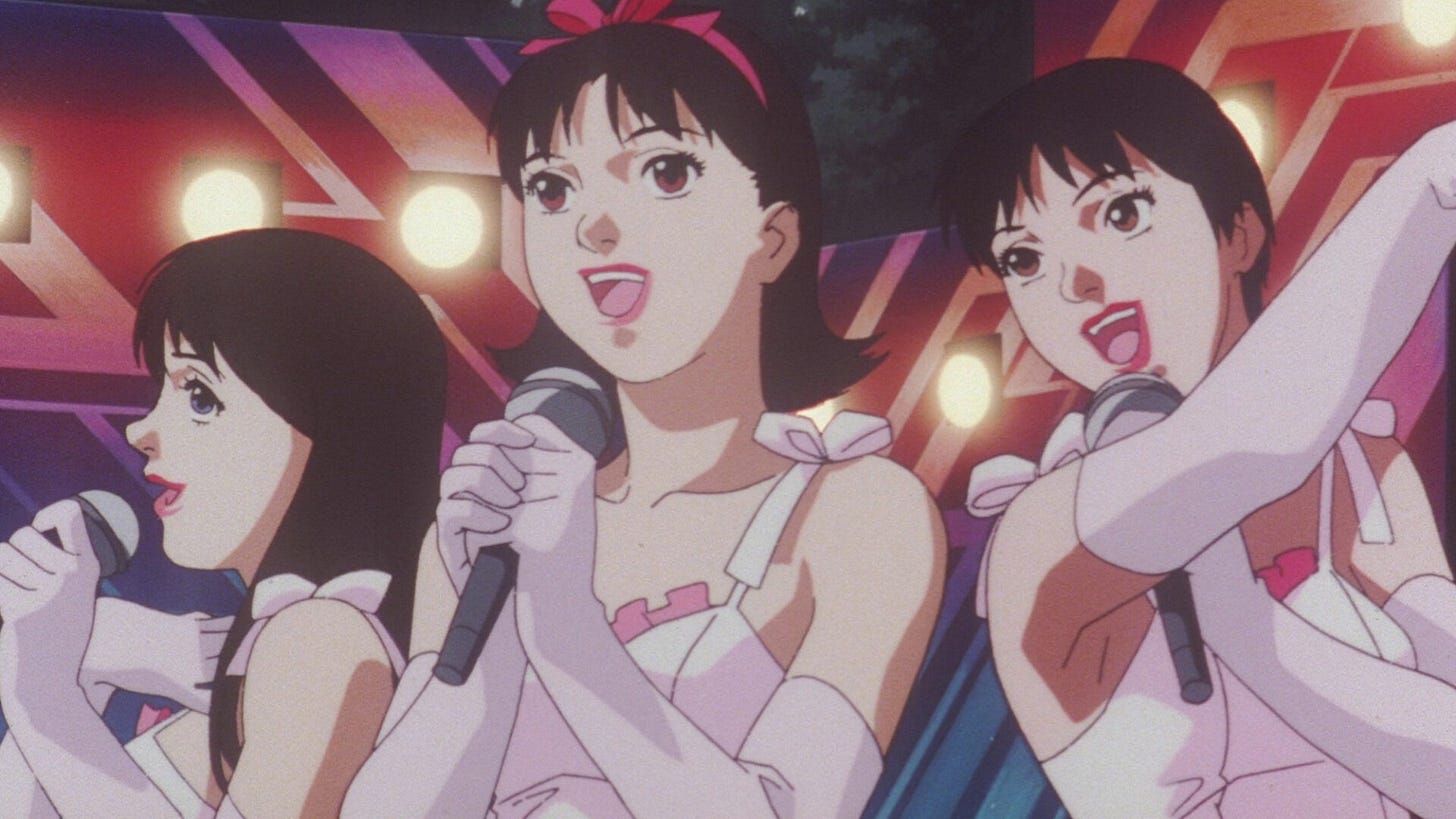

In 1997 Satoshi Kon directed his first feature length animated film, Perfect Blue. The film centers on Mima Kirigoe who leaves CHAM! to become an actress, assisted by Rumi Hidaka, a former idol who cares deeply for Mima. Obsessive fan Me-Mania is upset about her sudden change in image, writing upsetting letters to Mima about this. Mima finds a website called Mima’s Room, which strangely appears to be her own blog about her daily life.

—spoiler time—

She begins acting in Double Blind, with a graphic rape scene that affects her psychologically. She regrets her choices, falls into paranoia about the murders occurring around her, and obsession over the website. The character Mima plays in Double Blind is revealed to have Dissociative Identity Disorder, reflecting the actor’s deteriorating mental state. Black Swan is often compared to Perfect Blue for this similar type of plot centered around a protagonist losing their sense of self. Mima is hallucinating that another, better version of herself is taking over.

It is revealed that Rumi has an exact copy of Mima’s bedroom in her home, is running the website, and wants to replace Mima as an idol. The climax of the film involves a chase scene between Rumi (hallucinated by Mima to look like herself) and Mima. Rumi ends the film hospitalized, while Mima becomes an actress. All ambiguity and dissociation on her end appears to be cleared up.

Aesthetically, I adore this film, the 90s anime style of Satoshi Kon is nostalgic and beautiful. The art is blue, gray, with shocks of red throughout. The character are realistic, with iconic wide-set eyes. I often see Perfect Blue stills on mood boards with Serial Experiments Lain or Ergo Proxy, and along with some similar aesthetics, I wonder if the film’s inclusion of internet anxiety skews these films together in fans’ minds. Mima’s Room is a real website, which appears to be a transmedia marketing choice for the release of the US Blu-ray a few years ago.

Perfect Blue thrives on ambiguous narrative complexity, critiques idol culture, and the perception of innocence. It has a post classical mode of narration in the form of a puzzle film, but also a bit of a slasher. This film is somewhere between a 4 and 5 star for me, and is one I recommend to everyone who loves anime and horror.

You may have noticed that I did not mention the 2002 live action remake, and that is because I haven’t watched it yet, and it is in a lower tier on our iceberg. We will get to it eventually, but I have been told to keep those expectations low.

Sources:

Kon, Satoshi, director. Perfect Blue. Yamato, 1997.

Loriguillo-Lopez, Antonio, et al. “Making Sense of Complex Narrative in Perfect Blue.” Animation, vol. 15, no. 1, 2020, pp. 77–92., https://doi.org/10.1177/1746847719898784.

“Mima's Room.” Mima's Room, Gkids, 2018, https://mimasroom.com/.

Subissati, Andrea, and Alexandra West. “Candid Camera: Perfect Blue (1997) and Cam (2018).” Faculty of Horror, season 1, episode 93, 25 Feb. 2021.

Takeuchi, Yoshikazu, et al. Perfect Blue: Awaken from a Dream. Seven Seas Entertainment, 2018.

Takeuchi, Yoshikazu, et al. Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis. Seven Seas Entertainment, 2018.